TLDR

Even the most robust and mature software around us might have overlooked opportunities for better performance.

In this insight, I talk about how curiosity about a tool I almost always use for my web projects, called Rollup, led me to a 2x speedup optimization fix by simply taking a flamegraph and running an analysis. And how a slight skepticism led me to the realization that it’s actually not a 2x optimization fix.

Rollup is the mainstream bundler in the web community nowadays, a tool that takes a bunch of JavaScript files and other forms of assets and produces a bundle that combines many batches of these files into a few files optimized to run on most browsers and devices. So if you’re a web developer, there’s a high chance that you’ve worked with Rollup whether directly or indirectly through tools like Vite. Vite is also a well-known web development tool that smooths out the development experience by using another tool named ESBuild and relies on Rollup for production builds.

Vite’s performance in development was something totally peculiar for the industry. Development was powered by ESBuild, which itself was written in Go, and that partially explains the development speedup the community felt at the time. But even though production bundles were fast, they were not something that caught up to the development experience. Vite’s production bundles relied completely on Rollup, and the motivation behind this reliance is the maturity and edge-case richness it achieved across all these years of its existence, which goes back way before the initial releases of Vite and ESBuild.

The performance of Vite’s production builds is still bound to the speed of Rollup, which is built with JavaScript and therefore does not match the native speed of ESBuild.

The other issue with this separation is the inconsistency and divergence between development and production. This means you might hit issues in development that might not appear in production and vice versa.

So the potential for another speedup in production, and the homogeneity of development bundles and production bundles, motivated the team behind Vite to initiate an effort called Rolldown. A tool that matches Rollup’s maturity by being 100% compatible with it, and at the same time, catching up to the native performance ESBuild seizes, with the possibility of going even further.

Rolldown showed unbelievable signs with respect to performance, which made me wonder what was exactly going wrong with Rollup itself that did not make it as impressive performance-wise. I remember seeing a benchmark developed and maintained by the Rolldown team, which measured how bundlers behave with extremely large applications that constituted a complex module graph.

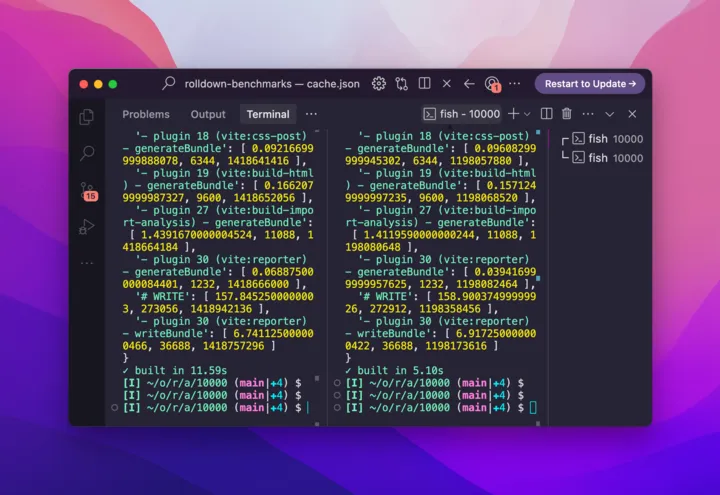

I chose the 10000 modules variant of the benchmark; running it with Vite (which, as mentioned, uses Rollup) on my system took 11 seconds, compared to Rolldown which does the job in less than one second.

Flamegraphs, The Easiest Way

Due to my past experience debugging performance issues, the first thing came to mind was capturing a flamegraph of Rollup’s bundling process using 0x.

0x is a JavaScript CLI tool that makes it easy to take flamegraphs.

pnpm dlx 0x -- node ../../node_modules/vite/bin/vite.js buildAs you can see, it mentions the Vite binary and not Rollup. The reason I did this was that Vite’s bundling process is mostly taken up by Rollup, so there should not be any mismatch between Rollup bundling and Vite doing the job itself as an abstraction over Rollup. Another bonus is that improving the Rollup usage in Vite improves both Vite and Rollup at the same time, so it’s a two-birds-one-shot game.

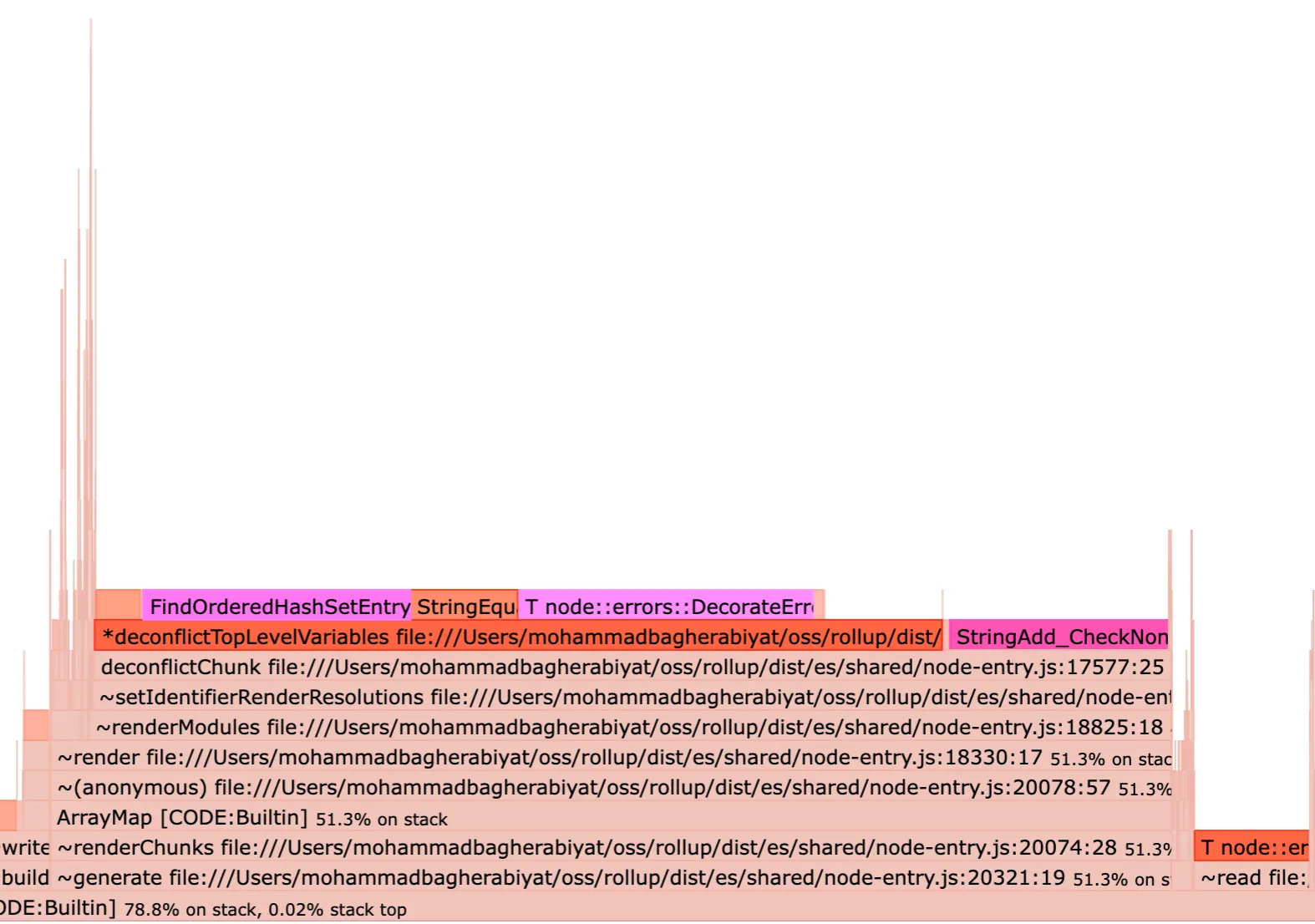

Here’s what I got.

The only thing I know for sure about flamegraphs is that the stronger the color is, the costlier that part is. I went with that intuition and found a function named deconflictTopLevelVariables having a pretty strong color.

Deconflicting

Checking the references to the function helped me understand the purpose behind it.

Bundling two files that use the same variable names can be an issue, since we can’t have two variables with the same name at the same scope.

// dep.js

const foo = 'dep';

console.log(foo);

export const bar = 'dep';// main.js

import { bar as baz } from './dep.js';

const foo = 'main';

const bar = 'main';

console.log(foo, bar, baz);Combining these two files together is not a trivial task and we can’t just concatenate them together. Doing so, without deconflicting, would cause the error Uncaught SyntaxError: Identifier has already been declared. Here’s where deconflicting comes in handy, it’s done so no two variables share the same name.

Here’s what the deconflicted output of those two files would look like:

const foo$1 = 'dep';

console.log(foo$1);

const bar$1 = 'dep';

const foo = 'main';

const bar = 'main';

console.log(foo, bar, bar$1);The deconflicting process iterates through all the variables, imports and exports, checks whether they require deconflicting, deconflicts them if needed and then captures them in a variable named usedNames. This is all happening in a small function called getSafeName.

export function getSafeName(

baseName: string,

usedNames: Set<string>,

forbiddenNames: Set<string> | null

): string {

let safeName = baseName;

let count = 1;

while (usedNames.has(safeName) || RESERVED_NAMES.has(safeName) || forbiddenNames?.has(safeName)) {

safeName = `${baseName}$${toBase64(count++)}`;

}

usedNames.add(safeName);

return safeName;

}Pointing back to the flamegraph, there’s an interesting keyword being highlighted above the deconflictTopLevelVariables row named FindOrderedHashSetEntry. This is the internal engine function behind usedNames.has(safeName) above. This indicates that looking up entries is contributing a lot to the computational cost of deconflictTopLevelVariables.

The most suspicious part of the function was the absence of caching.

Cache is Almost Always The Solution

General Advice: Whatever it is your program produces (pixels, files, anything), just make your program regenerate “the whole thing”, “every time”. Add caching and structural sharing of previous “versions” to make it fast. That’s it.

— Jordan Walke (creator of React), tweet

I recalled seeing a cache keyword somewhere in the Rollup or Vite docs, so I quickly searched it across the codebase and examined its usage. It was mainly being leveraged by subsequent builds in watch mode. Here’s what the docs say about it.

The

cacheproperty of a previous bundle. Use it to speed up subsequent builds in watch mode — Rollup will only reanalyse the modules that have changed. Setting this option explicitly tofalsewill prevent generating thecacheproperty on the bundle and also deactivate caching for plugins.

It struck me as such a low-hanging fruit. Here’s the method responsible for emitting the cache.

getCache(): RollupCache {

// ...

return {

modules: this.modules.map(module => module.toJSON()),

plugins: this.pluginCache

};

}And here’s toJSON which returns a serializable representation of a particular module.

toJSON(): ModuleJSON {

return {

ast: this.info.ast!,

attributes: this.info.attributes,

code: this.info.code!,

customTransformCache: this.customTransformCache,

dependencies: Array.from(this.dependencies, getId),

id: this.id,

meta: this.info.meta,

moduleSideEffects: this.info.moduleSideEffects,

originalCode: this.originalCode,

originalSourcemap: this.originalSourcemap,

resolvedIds: this.resolvedIds,

sourcemapChain: this.sourcemapChain,

syntheticNamedExports: this.info.syntheticNamedExports,

transformDependencies: this.transformDependencies,

transformFiles: this.transformFiles

};

}And yes, there’s nothing related to top-level variables specified here. So it’s a matter of adding a new record to store all the deconflicting effort we make in deconflictTopLevelVariables for each module. And let’s just name it safeVariableNames. The idea is to store each variable name as the key and the output of deconflictTopLevelVariables as the value of the record.

export interface ModuleJSON extends TransformModuleJSON, ModuleOptions {

+ safeVariableNames: Record<string, string> | null;

ast: ProgramNode;

...

}return {

...

+ safeVariableNames: this.info.safeVariableNames,

...

};Now the only thing remaining is the cache read and write operations in deconflictTopLevelVariables.

module.info.safeVariableNames ||= {};

const cachedSafeVariableName = Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(

module.info.safeVariableNames,

variable.name

)?.value;

if (cachedSafeVariableName && !usedNames.has(cachedSafeVariableName)) {

usedNames.add(cachedSafeVariableName);

variable.setRenderNames(null, cachedSafeVariableName);

continue;

}

variable.setRenderNames(null, getSafeName(...));

module.info.safeVariableNames[variable.name] = variable.renderName!;To retrieve from the cache, we do a lookup on the record we just defined for each module using variable.name, which is the current variable we’re deconflicting.

Initially, when I started the experiment, it was a basic module.info.safeVariableNames[variable.name] but that fails on edge cases where variable.name is equal to an object prototype property like constructor or toString.

If there’s a cached deconflicted name for the current variable and that cached version is not already used by another variable somewhere else, we use that cached name. variable.setRenderNames is just mutating the variable name to the deconflicted form.

If not, keep doing what we did previously using getSafeName but this time with a cache write so we can use it in subsequent builds.

Here’s a demonstration from the Rollup docs on how to use the cache property.

const rollup = require('rollup');

let cache;

async function buildWithCache() {

const bundle = await rollup.rollup({

cache // is ignored if falsy

});

cache = bundle.cache; // store the cache object of the previous build

return bundle;

}

buildWithCache()

.then(bundle => {

// ... do something with the bundle

})

.then(() => buildWithCache()) // will use the cache of the previous build

.then(bundle => {

// ... do something with the bundle

});The cache can be stored as a .json file somewhere or in CI/CD workflows like GitHub artifacts, and reused across all our builds and deployments.

Rollup will read options.cache and assign each module that’s being bundled the corresponding cached properties like safeVariableNames.

if (options.cache !== false) {

if (options.cache?.modules) {

for (const module of options.cache.modules) this.cachedModules.set(module.id, module);

}

}

const cachedModule = this.graph.cachedModules.get(id);

await module.setSource(cachedModule);

Why Does It Work?

This optimization would largely benefit applications with deconflicting as their bundle performance bottleneck—the kind that have numerous conflicting variable names.

Here’s a random component file from the Rolldown benchmark I optimized.

import React from 'react'

import I from '@iconify-icons/material-symbols/distance.js'

import { Icon } from '@iconify/react/dist/offline';

import C0 from './d4/f0.jsx'

import C1 from './d4/f1.jsx'

import C2 from './d4/f2.jsx'

import C3 from './d4/f3.jsx'

import C4 from './d4/f4.jsx'

import C5 from './d4/f5.jsx'

import C6 from './d4/f6.jsx'

import C7 from './d4/f7.jsx'

import C8 from './d4/f8.jsx'

function Component() {

return (

<div className="">

<C0 />

<C1 />

<C2 />

<C3 />

<C4 />

<C5 />

<C6 />

<C7 />

<C8 />

</div>

)

}

export default ComponentWe have approximately 10000 files with mostly the same exact content and the same component, import, and export names that only differ in the import paths. It has to be the case that deconflicting would be the bottleneck.

Benchmarks and The Question Mark

While writing this insight, I somehow turned skeptical of the optimization and whether the fix is going to be beneficial to everyone.

While analyzing the benchmark, I found out all the files share the same variable names, so the app has deconflicting as a bottleneck. Nearly 8 months after the optimization, and I just found this out. That’s why I appended the title with a question mark, because I felt the title should be part of the claim and not some flawed statement.

Was this joyful to come up with? YES. Is it beneficial to Rollup? Definitely. Is it beneficial to everyone using Rollup? Not sure about that.

And that’s the exact issue with most of the benchmarks in the industry. They’re too isolated and they almost always do not represent what happens in the real world.

Not only can they be biased toward a certain tool, but the isolation of the progress that happens within them is often overlooked. A 200% progress in a benchmark might mean nothing in the real world. That’s perhaps why Rollup was chosen for Vite. And perhaps why I’m optimistic about Rolldown, because the team behind it knows how to build for the real world the same way they did with Vite.

Potential

The neglected utilization of the cache option in Rollup is a sign to many more optimization opportunities. If you have an idea for a potential exploration path, please let me know so we come up with our own flamegraphs together and let the community benefit from the progress.

That’s what we do here at Thundraa, explore the unexplored paths with others and come up with something useful to us and the community.

Huge appreciation to btea and Amir for their reviews of this piece.

Thank you too for reading this! It’s Mohammad, and you can find me on GitHub, Bluesky, or X.